/RESEARCH

Data-Driven Science

Complex Network Reconstruction from Observables

Complex networks underpin diverse systems, from social interactions to neural circuits and power grids, where topology dictates dynamics like synchronization or information flow. Reconstructing these hidden structures from limited, coarse-grained data—such as aggregated time series or partial observations—poses a core challenge in network science, enabling predictions, diagnostics, and control.

Building on a prior work that infers network topology from synchronization motifs in oscillator ensembles under coarse graining, we developed a reservoir computing framework for robust reconstruction. Reservoir computing leverages a fixed, high-dimensional recurrent neural network (the "reservoir") to echo input dynamics, with only a linear readout trained to map observables back to edge weights or adjacency matrices. For simulated networks (e.g., Erdős-Rényi, scale-free), we feed node time series or lumped signals into the reservoir, optimizing for minimal reconstruction error via ridge regression. This approach excels in noisy, undersampled regimes, outperforming traditional inverse methods by capturing non-linear couplings and scaling to large graphs without explicit synchronization assumptions.

Preliminary results show accurate recovery of motifs like hubs and communities, with extensions to directed and weighted networks underway. Applications target real-world data, such as fMRI brain connectivity or financial correlations.

Ongoing research.

Spin Glasses

Spin Glasses: Phases in Frustrated Spin Systems

Spin-glass phases occur in magnetic materials where atomic spins freeze into a disordered state over time. This arises from frustrated interactions, where competing forces prevent uniform alignment, unlike in ferromagnets where spins line up consistently.

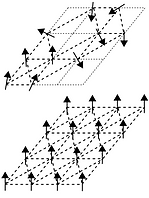

The left figure illustrates this: The top panel shows the random, patchy spin structure of a spin glass, with varying alignments across regions. The bottom panel depicts the ordered structure of a ferromagnet. These configurations in spin glasses change slowly, often on timescales longer than those observable in experiments, leading to gradual magnetization relaxation. Multiple equilibrium states with similar energies are possible, reflected in ground-state entropy introduced by random bonds and frustration.

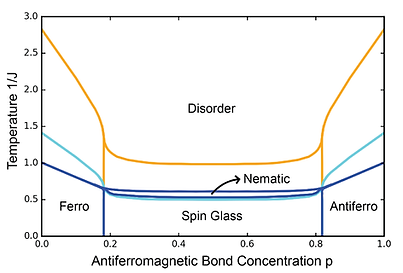

Spin-glass phases have been studied mainly in the spin-1/2 Ising model. Our work uses exact renormalization-group methods to determine the spin-glass phase and global phase diagrams in three dimensions for all spins s > 1/2. For each s, we identify chaotic behavior in interactions under scale changes.

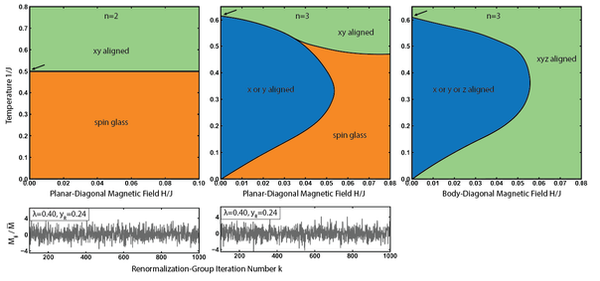

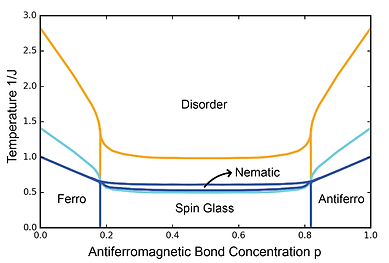

The right figure presents these phase diagrams for spin-s Ising spin glasses in 3D, showing transitions between ordered, disordered, and glassy states.

Spin Glass Machine: A Classifier for Complex Data

The Spin Glass Machine is a method we developed for classifying and grouping complex datasets. We tested it on music from different regions and cultures, as well as brain EEG signals. We have since applied it to other data, including COVID-19 patterns, music samples, and brain activity from fMRI scans.

The approach uses the chaotic behavior of spin glasses under scale changes to map complex data. This chaos creates fractal patterns, similar to those in real-world signals. We generate these patterns from renormalization-group calculations on frustrated hierarchical lattices, as shown in the upper left figure for Ising models and the upper right for the lattice structure.

%20Spin-Glass%20Behavior%20in%20Frustrated%20Ising%20Models%20with.png)

To classify data, we compare its fractal spectrum to those from spin-glass models. Parameters such as p, pb, pc, m1, and m2 identify the best match, projecting the data into a parameter space where groups form naturally.

In initial tests, the method separated music genres from Turkish and Western traditions into distinct clusters, with scatter plots showing clear patterns. For EEG data, it linked brain states during music listening to resting activity, particularly in frontal regions.

Spin-Glass Sponges: Surface Phases in Frustrated Systems

In spin glasses, we identified a new type of behavior called spin-glass sponges. We examined surface effects in these systems using exact renormalization-group methods on three-dimensional hierarchical lattices. A flat surface does not allow chaotic rescaling, so it lacks a surface spin-glass phase.

To address this, we proposed spin-glass sponges: structures with fractal surfaces of higher dimension, which are physically feasible. In these, higher sponginess leads to surface chaotic rescaling even without bulk chaos. We computed phase diagrams featuring a surface-only spin-glass phase, a combined surface-and-bulk phase, and a disordered phase. These three phases meet at a multicritical point M. Notably, chaos is stronger in the surface-only phase than in bulk-influenced cases.

Spin-Glass Phases under External Fields

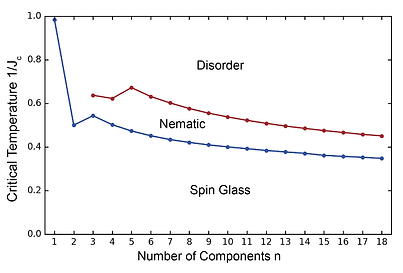

In magnetic materials known as spin glasses, atomic spins typically freeze into disorder without an external field. Our study of n-component cubic-spin systems in three dimensions reveals spin-glass phases that persist under applied magnetic fields.

We identified a nematic phase—similar to a liquid crystal—for systems with more than two spin components, appearing between the low-temperature spin-glass state and the high-temperature disordered state. Under uniform fields along axial, planar-diagonal, or body-diagonal directions, we found 17 distinct ordered phases and two types of spin-glass phase diagrams, differing from standard patterns. For the first time, we showed spin-glass phases under planar-diagonal and body-diagonal fields in two- and three-component systems. These arise from competition between aligned phases (along +x or +y) and alternating xy phases. We also computed chaotic rescaling behaviors and their rates in each diagram type, using renormalization-group methods exact on hierarchical lattices and approximate on cubic ones.

Liquid Crystal Phases in Spin Glasses

Liquid crystals represent a state of matter that combines features of liquids and solids. Molecules in this phase show partial order, like in crystals, while retaining the flow and mobility of liquids.

The nematic phase is a key example: Molecules align along a preferred direction, called the director, with long-range orientational order but no fixed positions. This allows parallel alignment without the rigid structure of a solid.

In our study of n-component cubic-spin spin-glass systems, we identified a nematic phase for n ≥ 3. It lies between the low-temperature spin-glass phase and the high-temperature disordered phase, fully separating the two. These results come from renormalization-group calculations, exact on hierarchical lattices and approximate on cubic lattices.

Criticality and Phase Transitions

Multicritical Orderings in Merged Spin Systems

Combining different spin models can produce outcomes greater than their parts, as complexity predicts. We merged Potts and clock systems—featuring permutation-symmetric and spin-rotation-symmetric interactions—and calculated global phase diagrams in two and three dimensions. This used renormalization-group methods with the enhanced Migdal-Kadanoff approximation, which identifies spontaneous first-order transitions, or equivalent hierarchical lattices including effective vacancies.

Five ordered phases emerge that do not exist in the separate models: ferromagnetic, quadrupolar, antiferromagnetic with conventional ordering, and antiferromagnetic and antiquadrupolar with algebraic ordering. These, along with the disordered phase, are divided by first- and second-order transitions. Multicritical points bound them, including inverted bicritical, zero-temperature bicritical, tricritical, second-order bifurcation, and zero-temperature highly degenerate points. One phase diagram topology captures all these elements

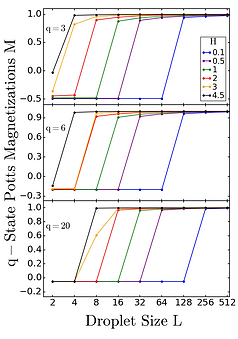

Nonequilibrium Phase Transitions: Metastable Droplets in Spin Systems

Nonequilibrium systems arise when microscopic processes break detailed balance, meaning probability flows between states do not cancel out. These conditions are common, as equilibrium is rare, and structural changes often happen far from it.

While equilibrium critical phenomena show universal traits from large-scale fluctuations, nonequilibrium ordering remains less understood. Similar fluctuation mechanisms may apply here, revealing shared or unique properties. One example is the disappearance of metastable droplets—temporary clusters of a non-stable phase persisting in a stable one. We extended equilibrium renormalization-group methods to study these droplets' properties in nonequilibrium settings.

Using finite-system renormalization-group theory, we examined q-state Potts models in three dimensions. We determined the existence and boundaries of metastable droplets, along with how their critical sizes depend on magnetic field, temperature, and q. The same approach calculated hysteresis loops across first-order transitions, showing loop sizes and shapes as functions of these parameters. We observed asymmetry in the loop branches. The method extends to critical behaviors in metastable phases, such as surface-adsorbed systems or water.

Total Thermodynamics at and away from Phase Transitions

Renormalization-group methods, first developed for critical phenomena, can compute the full thermodynamics of a system, including regions far from phase transitions. This requires recursion relations for local densities, making the calculations more involved than those for phase boundaries or critical exponents.

We performed these calculations for q-state Potts and clock models in three dimensions. Using exact renormalization-group approaches on hierarchical lattices and the Migdal-Kadanoff approximation on cubic lattices, we determined all local bond-state densities.

Key results include reentrant behavior in interface densities under symmetry breaking: As temperature decreases, the density rises initially before falling to zero at absolute zero. We proposed a physical mechanism for this pattern. We also identified differences in phase transitions between the models, attributed to alignment and entropy effects as q approaches infinity.

The figure displays nearest-neighbor densities for the q-state Potts model (left) and clock model (right) in 3D.

Phase Transitions in Continuous-Spin Spin Systems

Continuous-spin models in statistical mechanics describe spins as vectors free to rotate continuously in a plane (XY model) or three dimensions (Heisenberg model), unlike discrete models such as Ising where spins flip only between up and down. This freedom introduces richer dynamics: In two dimensions, true long-range order is absent at finite temperatures due to thermal fluctuations, but algebraic order—characterized by power-law decay of correlations—can emerge. Phase transitions often involve topological defects like vortices, unbound at high temperatures and bound at low ones, as in the Berezinskii-Kosterlitz-Thouless mechanism. These models apply to superconductors, liquid crystals, and planar magnets, highlighting universal behaviors distinct from discrete counterparts.

We studied the Ashkin-Tellerized XY model, with two continuous XY spins per site (orientations from 0 to 2π) linked by two- and four-spin interactions. Position-space renormalization-group analysis, exact on hierarchical lattices and approximate on square lattices, revealed fixed lines of continuously varying potentials yielding multiple algebraic orders: ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic in individual spins, and in their product. Each ties to unique Berezinskii-Kosterlitz-Thouless fixed potentials. Criticality evolves along these lines, with flows expressed through doubly composite Fourier coefficients of the exponentiated four-spin energy. The disordered phase borders two semi-infinite quasi-disorder lines.

Long-Range Interactions in Spin Systems

In low-dimensional systems, short-range interactions typically prevent long-range order at finite temperatures, as thermal fluctuations disrupt alignment. However, power-law decaying long-range couplings extend influence across distances, potentially stabilizing ordered phases and altering critical behaviors. This interplay between dimensionality and interaction range reveals universal principles in phase transitions, applicable to magnets, neural networks, and quantum materials.

We analyzed the one-dimensional Ising model with such interactions (J r^{-a}) for all exponents a, using renormalization-group methods that project both ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic tendencies. For ferromagnetic interactions (J > 0), a finite-temperature ordered phase exists for 0.74 < a < 2, with second-order transitions; the temperature decreases monotonically, becoming first-order at a = 2 and vanishing for a > 2, as rigorously predicted. As a approaches 0.74 from above, the transition temperature diverges, yielding order at all finite temperatures—entering a mean-field-like regime before interactions equalize fully. Critical exponents (α, β, γ, δ, η, ν) vary continuously with a.

For antiferromagnetic (J < 0), frustration from competing triplets across all ranges prevents any ordered phase. In the spin-glass case, with random ferromagnetic/antiferromagnetic bonds, a finite-temperature spin-glass phase emerges without antiferromagnetic order. Chaos under scale changes is amplified, affecting interactions at every separation for a piecewise chaotic profile.

The figures illustrate phase diagrams, transition temperatures, critical exponents, and chaotic flows.

Extending this framework to the Blume-Emery-Griffiths (BEG) model—a spin-1 generalization incorporating bilinear, biquadratic, and crystal field interactions—yields comparable yet enriched behaviors. This research is currently under operation.

Complexity of Sociopolitical Systems

Self-Organized Criticality in Sociopolitical Movements

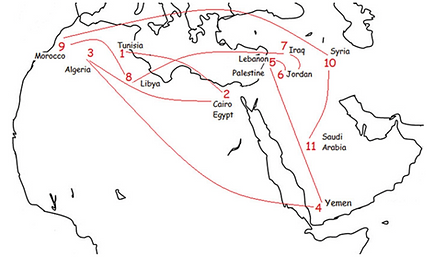

In an increasingly connected and globalized world, traditional frameworks for analyzing social dynamics often fall short. Complexity science provides tools to uncover hidden mechanisms behind observable events. Self-organized criticality (SOC) is one such concept: It views society as a system that naturally evolves toward a critical state, where small triggers can spark large-scale reorganizations, akin to phase transitions in physics.

A system is self-organizing if its components produce emergent patterns at larger scales. It reaches criticality under specific conditions, poised for abrupt change. We apply SOC to sociopolitical events, arguing it better captures how fragile structures amplify triggers into widespread movements.

For the Arab Uprising, SOC reframes the initial Tunisian protest not as a random start but as a tipping point in a society already at criticality. This lens highlights underlying fragilities—economic, social, and political—rooted in shared histories, cultures, and regional ties. It contrasts with chaos theory's "butterfly effect," which overlooks the system's preparatory state.

The right figure maps the protests' chronological spread, illustrating regional interconnectedness: Events cascaded across borders, revealing how local sparks ignite broader chains in interdependent networks.

Whether the Uprising marked a "spring" toward renewal or a "fall" into turmoil depends on the phase transition's outcome. Understanding these dynamics aids in grasping societal intentions and potential futures.

Complexity in Governance and Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic affected countries differently, shaped by variations in social norms and governance. This diversity creates a complex dataset that benefits from quantitative analysis to identify underlying patterns.

We used the Spin Glass Machine to examine correlations between governance indicators and COVID-19 outcomes in 180 countries from January 1, 2020, to February 27, 2022. Indicators included control of corruption, political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, voice and accountability, government response, and government-response time, drawn from World Bank data. COVID-19 cases and deaths came from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker.

The method computes multifractal spectra from time series data and matches them to spin-glass chaos projections, mapping countries into a parameter space (m₁ and p_b). Scatter plots reveal two main clusters per indicator: High-governance countries (top quartiles) form a diagonal line in upper regions, while lower-governance ones cluster horizontally below. Overlaps in projections show shared multifractal behaviors across diverse nations, with no strict ties between governance metrics or income levels. Distances between case and death projections highlight similarities or differences in patterns.

These results indicate governance influences pandemic outcomes through non-linear, fractal-like dynamics, with high governance linked to distinct clusters.

Chaos and Complexity in Condensed Matter

Liquid Crystal in a Dirty Magnet

In disordered magnetic systems, known as "dirty" magnets due to quenched randomness, liquid-crystal-like phases can emerge. These combine partial order with fluidity, similar to how molecules in liquid crystals align directionally without fixed positions.

We found a nematic phase in n-component cubic-spin spin-glass systems for n ≥ 3 in three dimensions. It positions itself fully between the low-temperature spin-glass phase and the high-temperature disordered phase, acting as an intermediate liquid-crystal state in this disordered environment. Results stem from renormalization-group calculations, exact on hierarchical lattices and approximate on cubic lattices.

Additionally, we computed Lyapunov exponents—a measure of chaotic behavior in spin-glass dynamics—from n = 1 to n = 12. These exhibit odd-even oscillations with respect to n, highlighting sensitivity to the number of components.

q-Statistics of Chaotic Behavior in Transient Current Through Thin Films

Near thermodynamic equilibrium, Boltzmann-Gibbs statistics describe systems with Gaussian distributions, linking microscopic dynamics to macroscopic properties via equations like the Boltzmann transport equation. Far from equilibrium, complex systems with long-range correlations, multifractality, and non-Gaussian tails require unified statistics and dynamics. Tsallis statistics extend this framework by generalizing entropy, yielding q-distributions—peaked curves with power-law tails (as in the below figure)—that capture chaos and multifractals.

We applied q-Gaussian analysis to transient currents through thin films of As₂S₃(Ag) and As₂Se₃(Al) chalcogenites, materials with multifractal structures supporting multiple conduction paths. Differences in successive current values were normalized, histograms formed, and distributions fitted to q-Gaussians. Fits were superior to standard Gaussians, with q > 1 (q=2.5 for As₂S₃(Ag), q=2.7 for As₂Se₃(Al)), indicating weak chaos and long-range correlations. The slight q difference suggests weaker interatomic attractions in As₂S₃(Ag). These results align with prior chaos analyses, confirming intermediate-dimensional chaotic behavior in two correlation regimes.

Chaotic Behavior in Transient Current Through Thin Films

Chaotic systems appear random but follow deterministic rules highly sensitive to initial conditions. Small variations, like measurement errors, lead to vastly different outcomes over time, making long-term predictions challenging despite their rule-based nature. These systems often show patterns such as fractals, self-similarity, and feedback loops.

The left figure illustrates this sensitivity: Two trajectories, differing by just 1% in initial conditions, diverge dramatically after a period.

Controlling such chaos is key for reliable devices like sensors using materials that exhibit irregular currents under electric fields. We analyzed transient currents in thin films of As₂S₃(Ag) and As₂Se₃(Al) chalcogenides, known for dielectric properties and non-linear conduction. Samples were metal-glass-metal structures with 300 nm aluminum electrodes, measured via automated I-V setups at constant voltage.

Using time-series methods—rescaled range analysis, mutual information, false nearest neighbors, and Lyapunov exponents—we identified two fractal regimes: short-time relaxation (stretched exponential or logarithmic) and long-term chaos. Hurst exponents above 0.5 indicated long-range correlations. Positive Lyapunov exponents (0.317 for As₂S₃(Ag), 0.456 for As₂Se₃(Al)) confirmed chaotic stretching, with embedding dimensions around 10. These findings reveal intermediate-dimensional chaos in chalcogenide conductivity.

Quantum Electronics

Transport Properties of Quantum Point Contacts (QPC)

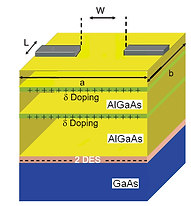

Quantum point contacts (QPCs) are narrow constrictions in two-dimensional electron systems (2DES), enabling the study of charge transport in mesoscopic conductors. Beyond fundamentals, QPCs serve as sensitive detectors for single electrons and as readout devices for qubits in quantum computing—a qubit being the basic unit of quantum information.

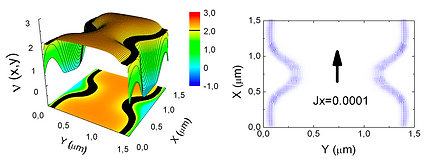

2DES form at heterostructure interfaces (left figure), with QPCs created via surface gates for electrostatic confinement or chemical etching. The constriction's nanoscale size quantizes energy levels perpendicular to current flow, allowing transport only when electron energies match these levels. At low bias, conductance steps in integer units if energies align; below the lowest level, no current passes.

Conductance sensitivity to constriction size makes QPCs ideal for detecting nearby potential fluctuations. A perpendicular magnetic field adds further quantization via the quantum Hall effect, forming discrete Landau levels (LLs) like a harmonic oscillator spectrum. At fixed electron density, the Fermi energy (E_f) either pins to an LL (compressible state, allowing redistribution) or lies between LLs (incompressible state, with no states at E_f for equilibrium). Incompressible regions show vanishing resistivity due to absent scattering, confining current there.

We investigated 2DES transport under QPCs and magnetic fields to control currents for quantum information processing, focusing on equilibration conditions between compressible and incompressible regimes.

This research, conducted in 2010-2011, highlighted QPCs' potential for qubit readout at a time when quantum computing was emerging from theoretical foundations into experimental demonstrations, such as D-Wave's release of the first commercial 128-qubit annealer and reports of entanglement in solid-state spin ensembles. Back then, systems were limited to small qubit counts with high noise, far from scalability. In 2025, the field has matured significantly, with hundreds of qubits in play, progress toward error correction in platforms like Google's Willow and IBM's Majorana 1, and global recognition via the UN's International Year of Quantum Science and Technology. QPC-based charge sensing remains crucial for high-fidelity readout in solid-state qubits, though now integrated with advanced techniques to support fault-tolerant computing.